After the devastating fire at Tai Po, Hong Kongers are demanding accountability. The city’s grief has transformed into visible outrage as thousands gather to honor the 156 lives lost in the blaze at Wang Fuk Court. Along the riverbank leading to the charred towers, mourners formed long lines, clutching white flowers, their faces marked by tears and disbelief.

Families, neighbors, and strangers alike paused before the ruins, some shaking their heads, others silently weeping. Yet grief alone does not define the scene. Anger cuts through the solemnity, directed at authorities perceived as unresponsive. As the city mourns, the government responds with intensified measures to suppress public dissent, escalating tensions, and deepening the wounds left by the tragedy.

Read More: NATO Chief Reassures Allies on U.S. Commitment to Ukraine

An Avoidable Disaster Years in the Making

As the scale of the Tai Po fire became clear, questions about preventability intensified. The Labour Department, responsible for construction safety, confirmed it had received repeated complaints from residents about the estate’s scaffolding and mesh since last year. Inspectors reportedly visited the site several times, most recently on November 20, issuing warnings to the contractor but failing to enforce compliance.

Local media reported that Tai Po district councillor Peggy Wong had acted as a consultant to the renovation company, though Wong denies involvement. Officials later discovered mesh at the site that failed fire safety standards. Police have arrested 13 people linked to the construction firm, with the government accusing the company of “gross negligence.” City leader John Lee pledged accountability, announcing an independent review committee chaired by a judge and acknowledging “systemic” lapses in oversight.

Public skepticism remains high. “It’s ridiculous,” said Janet Chung, a daily visitor to the memorial site, questioning how police could arrest suspects mere hours after the blaze began. She criticized government claims that bamboo scaffolding was the cause, insisting the real issue was corruption. Others have voiced similar concerns, noting the danger of openly criticizing authorities.

Journalist Kris Cheng, who has covered Hong Kong for years, highlighted long-standing structural problems: corruption in construction bidding, reliance on cheap labor, and use of substandard materials. “These issues have been known for years,” Cheng said. “Ironically, some who raised them are now imprisoned for their political activities.”

The Arrest of Miles Kwan

Miles Kwan handed out leaflets to anyone willing to take them. On Friday night, two days after the fire, he positioned himself at the main exit of the busy Tai Po MTR station, as commuters hurried past. “We Hong Kongers are united in grief, united in anger about this fire,” Kwan told Hong Kong Free Press. His leaflets laid out four demands for government accountability, including an independent inquiry into the blaze. “If the government interprets these simple demands as inciting hatred, that would be very oversensitive,” he said.

Kwan’s call for accountability resonated widely. A student-led petition supporting his demands gained 10,000 signatures within 24 hours, amplified across social media. But by Saturday evening, the petition disappeared. The South China Morning Post reported that Kwan had been arrested for sedition, a charge that can carry up to 10 years under Hong Kong’s national security law. On Monday, he was photographed leaving a police station.

In the following days, two more individuals were arrested for sedition, including a former pro-democracy district councillor. At a press conference, city leader John Lee did not address individual cases, but warned: “We will show no tolerance for those who disrupt unity now, who exploit this tragedy.” Beijing’s national security office in Hong Kong issued similar warnings to “anti-China disruptors,” promising enforcement of the law’s “full force.” Meanwhile, the state-run China Daily editorialized on Kwan’s petition, accusing actors of attempting to “tear society apart under the guise of petitioning.”

Behind the Crackdown

“This says a lot about the shrinking space for freedom of expression in Hong Kong,” said Alan Tan, a political commentator who requested a pseudonym. “What they fear most is Kwan’s call for an independent investigation. The government is paranoid about a commission that could summon its own officials.”

The commission announced by John Lee lacks such powers. It cannot compel officials to testify or punish refusals. Although Lee acknowledged the need for systemic reform in Monday’s speech, he insisted the review would be sufficient.

Journalist Kris Cheng said Kwan’s arrest was predictable. “These arrests create a climate of fear,” he said. “The government allows public mourning, but anger cannot be expressed openly,” Cheng added that Hong Kongers are furious because the fire was likely preventable, yet those speaking out face imprisonment.

Cheng noted that authorities likely reacted swiftly because Kwan’s “four demands” echoed the “five demands” central to the 2019 anti-government protests—a topic still highly sensitive. The protests of 2019–2020 escalated into widespread clashes, ending with the passage of the National Security Law, which critics warned would silence dissent.

A crackdown on civil society and democratic institutions under the then-security minister John Lee prompted a wave of pro-democracy emigration. Now city leader, Lee has continued to tighten control over speech, though he maintains Hong Kongers retain the right to express opinions freely, framing the National Security Law as a tool to preserve “order and prosperity” in close alignment with Beijing.

Tight Control – Inspired by the Mainland

“In Hong Kong, we’re seeing a very Chinese approach: crushing dissent by force,” said Emma Smith, a financial professional who witnessed the 2019 pro-democracy protests firsthand. Speaking on condition of anonymity, she added, “Because Hong Kongers still have some guaranteed rights under the Basic Law, the government relies on the vague National Security Law as a workaround. And it works perfectly for trampling people’s rights.”

Journalist Kris Cheng echoed her assessment: “Officials in Hong Kong now routinely mirror Beijing’s rhetoric, prioritizing ‘stability maintenance’ over transparency. This is very much the Chinese model.”

Cheng noted that the crackdown also reflects lessons Beijing has drawn from its own protest movements. He cited the 2022 White Paper Movement, when young people took to the streets holding blank sheets of paper—a rare, open challenge to Xi Jinping’s rule. “It all started with a mishandled fire in an apartment block in Ürumqi,” Cheng said. “The Chinese government understands how such incidents can ignite broader unrest.”

Echoes of a Different Time

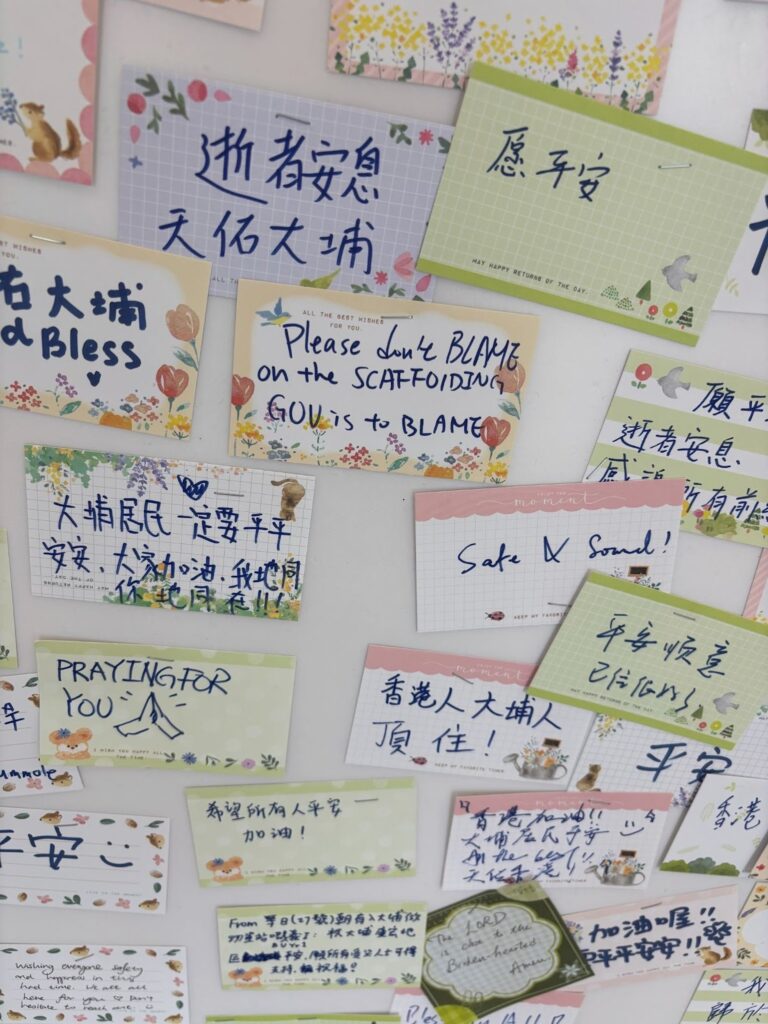

Despite the climate of fear, a resilient spirit persists. Across Hong Kong, “Lennon walls”—styrofoam boards for anonymous post-it messages—have reappeared, echoing 2019’s pro-democracy movement. Many now carry defiant messages responding to the Tai Po fire, a visible sign that dissent finds ways to surface even under intense pressure.

Volunteers quickly mobilized at the fire site, organizing aid and supplies for victims and first responders through social media, bridging communities across the city. “This is the Hong Kong spirit,” said Faisal, an imam at a mosque near Tai Po, who had returned to the site for the third time on Sunday, bringing Pakistani food for the displaced. “Everyone helps together here, no matter where you’re from. We don’t need a leader for that.”

An Election Few Expect Much From

Around Wang Fuk Court, election posters remain, a reminder that Hong Kong’s Legislative Council vote is scheduled for December 7. But the political landscape has been dramatically reshaped. Following a sweeping overhaul, the public now elects fewer representatives, and all candidates must be vetted by a committee to ensure only “patriots” govern.

“It will not be an enthusiastic event,” said Tan. The previous election under the new system saw record-low turnout, and despite free transport and celebrity campaigns, he predicted widespread apathy. “The future of democratic development is bleak.”

Cheng added, “The fire gives authorities an excuse for low turnout. They can pretend everything is back to normal afterward.”

Back in Tai Po, the election feels distant. Janet Chung laughs bitterly when it is mentioned. “When is that even? They have to have it, I guess.” At the square beneath the towers, once swarming with volunteers, government staff now manage the flow. After waiting over an hour, mourners are given barely twenty seconds to lay flowers before being ushered away. They have been granted a measure of grief—but nothing more.

Frequently Asked Questions

What caused the Tai Po fire?

The fire at Wang Fuk Court remains under investigation. Early reports indicate unsafe construction practices, including improperly installed scaffolding and mesh, may have contributed. Officials found materials at the site that did not meet fire safety standards.

How many people died in the fire?

As of the latest reports, 156 people lost their lives in the fire.

Why has the government cracked down on protests and petitions related to the fire?

Authorities have cited the National Security Law, which allows charges such as sedition. Individuals like Miles Kwan were arrested for calling for independent investigations, as the government views such actions as threats to “stability.”

What is the independent review committee announced by John Lee?

The committee is tasked with investigating the fire, but it lacks the authority to compel testimony or punish officials who refuse to answer questions. Officials describe it as sufficient for accountability, but critics argue it falls short of a truly independent inquiry.

How has public mourning manifested despite the crackdown?

Mourners have created memorials, laid flowers, and posted messages on “Lennon walls.” Volunteers have organized aid for victims and first responders, showing community solidarity even under restrictive conditions.

How does the political system in Hong Kong affect elections?

Following a recent overhaul, public elections now involve fewer directly elected representatives, and all candidates are vetted to ensure only “patriots” can run. Critics predict low voter turnout and limited democratic development.

Conclusion

The Tai Po fire is more than a tragedy of flames and loss; it is a mirror reflecting the deep fractures in Hong Kong’s society and governance. Grief, anger, and solidarity converge at the charred towers, revealing a community that mourns collectively even under the watchful eyes of authorities. The swift arrests, controlled investigations, and political constraints highlight a city grappling with restricted freedoms and heightened oversight.